If you can’t say that nuclear war is impossible, then you must think about it. The consequences are just too dire. This was the view of Herman Kahn, a leading nuclear strategist at the Rand Corporation – a group of American nuclear strategists and defence intellectuals who dedicated their lives to thinking about the unthinkable – nuclear war with Soviet Russia.

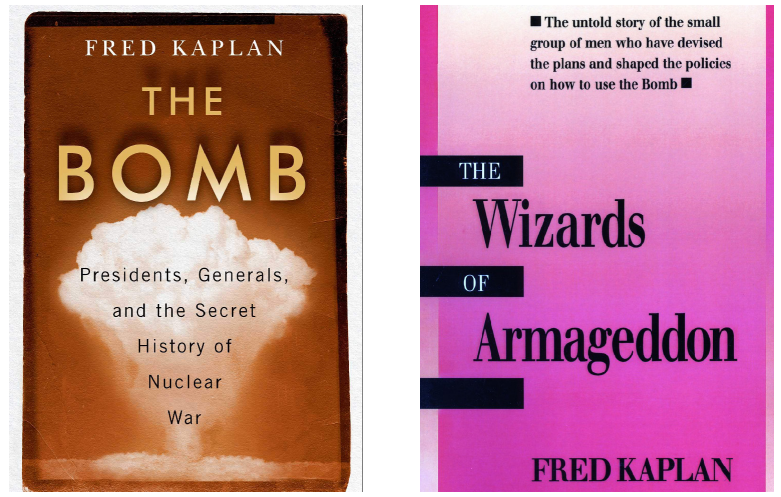

Fred Kaplan in his book, The Wizards of Armageddon (1991), intricately documents the secretive history of these men and their influence during the Cold War. Throughout the book, these strategists struggle with a singular problem: how to bring nuclear war down to human proportions – how to put a ‘rational’ framework around something so destructive.

To create this framework, RAND’s planners used the tools of the modern economist: utility functions, payoff matrices, and game theory. In the 1960s, the dominant framework for thinking about nuclear war at the RAND corporation was called counterforce. Rather than obliterating as much of the USSR as possible, counterforce ‘restrained’ America to targeting Soviet military and nuclear capabilities only. This would leave a large reserve force of nuclear weapons that could be used to destroy cities if the Russians retaliated. Russian cities would be ‘held hostage’, forcing the Soviet Union to the negotiating table. The work of RAND, led by Bill Kaufmann, revealed that a counterforce strike could save 100 million lives as compared to a full nuclear exchange.

Counterforce contrasted with the military’s approach: a strategy of maximum destruction in order to deter war in the first place. ‘Restraint’ was anathema to that view. Kaplan describes the striking story of what happened when these views clashed. Bill Kaufmann, representing RAND, was supposed to brief General Power, head of American strategic forces, on counterforce.

Barely a couple of minutes into the briefing, General Power interrupted, “Why do you want us to restrain ourselves? Restraint! Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards!” He continued, “Look. At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win!”

The mushroom cloud rises over Nagasaki after the atomic bomb exploded.

Kaufmann retorted, “Well, you’d better make sure that they’re a man and a woman”. General Power left the room; the briefing was over. Kaplan’s book presents both disturbing conversations and unsettling analysis in equal measure. Besides the targeting of nuclear weapons, the next most contentious debate concerned how many nuclear weapons were necessary. Analyses of strategies and their weapon requirements informed contentious wrangling over the defence budget. Sometimes the analysis of these strategies would not be out of place in a first-year economics course.

In 1961, the military, government, and defence intellectuals that helped influence that year’s defence budget all agreed that 400 megatons was enough to deter the Soviet Union from attacking the United States. It was agreed that 400 megatons would be enough to deal a catastrophic blow to the Soviet Union. This strategy was called ‘Assured Destruction’. Yet, this number – 400 megatons – was not derived from deterrence or strategic thought, but a more familiar concept to undergraduate economists – diminishing marginal returns.

After 400 megatons (pictured below), the defence intellectuals believed that extra bombs dropped would have only limited effectsbecauseofthe‘kink’ inthegraph.This truly puts the ‘dismal’ in the ‘dismal science’. Civilians agreed: ‘assured destruction’ was renamed ‘Mutually Assured Destruction’ and given the acronym MAD.

There is rarely a good ending to this story. In Kaplan’s latest book, ‘The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War’, he finds one uplifting story to tell centred on a private conversation between President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev at the 1985 Geneva summit.

During that conversation Reagan turned to Gorbachev and asked, “What would you do if the United States were suddenly attacked by someone from outer space? Would you help us?'

Gorbachev replied, “No doubt about it." Reagan replied, 'We too.'"

"So that's interesting," Gorbachev said to much laughter.

Human moments like this one can have an impact. Soon afterwards, Reagan added the following to his 1987 speech to the UN:

“Perhaps we need some outside universal threat to make us recognize this common bond. I occasionally think how quickly our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world.”

If you are interested in how economic tools have been used to advise governments on nuclear policy, then Fred Kaplan’s excellent books are worth studying. Kaplan explains how the Americans approached, and presumably still approach, nuclear war.

The B-47 was the main aircraft of choice for Strategic Air Command (SAC) during the early Cold War.

Originally published in 1983, the Wizards of Armageddon remains one of the most authoritative books on the men behind the nuclear age. Kaplan’s second book on the topic, The Bomb (published 2020), brings the story all the way up to Trump.