文章目录[隐藏]

- Scientific Theorization and Evaluation

- Philosophical Theorization and Evaluation

- The First Condition: Roles Both Observation and Intuition Serve

- Observation’s Roles: Explanandum and Evidence

- Intuition’s Role: Explanandum and Evidence

- The Second Condition: Roles Only Intuition Serves

- Intuition as the basis of philosophical theories

- Conclusion

- 科学理论与评价

- 哲学理论与评价

- 第一个条件:观察和直觉的作用

- 观察的作用:解释和证据

- 直觉的作用:解释和证据

- 第二个条件:只有直觉服务于角色

- 直觉作为哲学理论的基础

- 结论

题目:Is intuition to philosophy as observation is to science?

翻译:直觉之于哲学就像观察之于科学吗?

原文

When asked what characterizes the empirical sciences, it is often said that its reliance upon observations serves as the answer. When the same is asked of philosophy, many philosophers hold that the answer lies in philosophy’s dependence upon our intuitions. Naturally, then, the question arises: is observation to science as intuition is to philosophy? To answer this question, I will analyze and compare the roles assigned to observation and intuition in science and philosophy, respectively. After such examination, I come to the conclusion that as there are roles that only intuition serves and not observation, their contributions in their respective fields are not analogous to each other.

Before discussing what roles intuition and observation have, however, it must first be granted that the two do indeed have their places in scientific and philosophical inquiry. As such, the scientific and philosophical method and whether observation and intuition contribute to them must be examined beforehand.

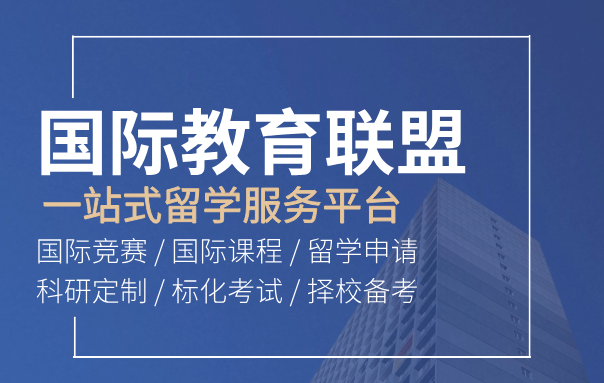

Scientific Theorization and Evaluation

The scientific method, in contemporary literature, is identified with two steps: theorization and evaluation (Dorling & Miller, 1981; Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002). Scientists first start their inquiry by postulating rational theoretical systems that, in accordance with reason, explain observations (Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002; Staley, 2014). In the process, scientists follow what I call Theory Constructing Principles (TCPs). TCPs are the necessary principles of reason[1] that allow scientists to think rationally. Without TCPs, the very rules of reason, no rational theorization can take place. Thus, by constructing rational theories, all scientists follow TCPs.

After scientists hypothesize theories, they discern the most plausible ones.[2] They carry out this evaluation by using what I call various Theory Evaluation Principles (TEPs): generally, scientists prefer theories that do not contradict empirical observations, that are falsifiable, precise, parsimonious, and in agreement with corroborated theories (Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002). Theories displaying these virtues laid out in TEPs, are favored over theories that fail to do so. As both theory construction and evaluation are closely related to observation, it seems reasonable to conclude that observation is at the core of the scientific method.

Philosophical Theorization and Evaluation

Philosophers generally believe that philosophical inquiry can be broken down into three major steps: philosophers first canvass intuitions, then construct rational theories that systematize them, and lastly evaluate their plausibilities (Bealer, 1998). Simply put, philosophical inquiry also involves a theorization-and-assessment process.

As there cannot be any form of rational theorization without the basic principles of reason, philosophers—in constructing rational theories—follow TCPs as well. Furthermore, after their construction, philosophical theories undergo an evaluation process in which philosophers apply their own TEPs: generally, philosophers prefer theories that are largely in agreement with intuitions, that are precise and ontologically parsimonious (Carroll & Markosian, 2010; Pust, 2000). As such, intuition also is deeply connected with the philosophical method in both the theory construction and evaluation process. Therefore, it seems, observation and intuition have their rightful places in science and philosophy, respectively.

With this established, to answer the question on whether intuition in philosophy is analogous to observation in science, I will specify the conditions that allow intuition to be similar to observation. If intuition in philosophy lacks the epistemic status observation enjoys in science, or vice versa, an affirmative answer to the question will not be available. Thus, in order for one to be justified in claiming that intuition’s role philosophy is similar to observation’s role science, intuition must satisfy the two following conditions:

Intuition in philosophy must not lack any of the roles taken up by observation in science.

2. Intuition’s role in philosophy must not exceed the roles taken up by observation in science.

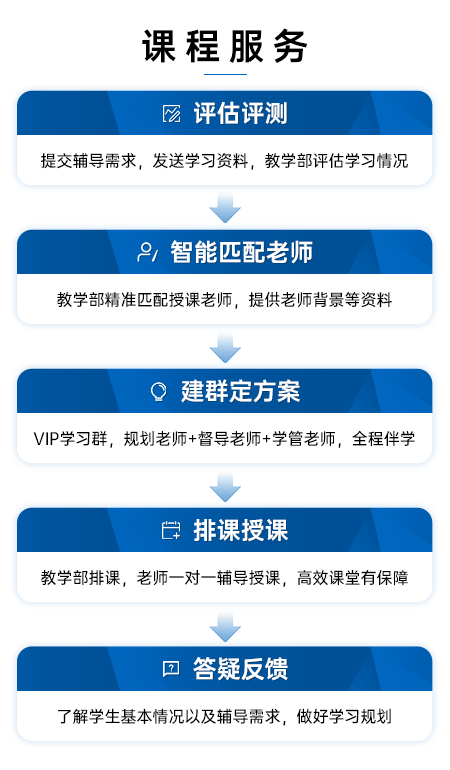

The First Condition: Roles Both Observation and Intuition Serve

Observation’s Roles: Explanandum and Evidence

As mentioned before, theories exist as the explanans that explain observational data. Consequently, in constructing theories, observation takes on the role as the explanandum, i.e., that which is to be explained. As the purpose of a theory lies in explaining observational data, observation is one of the most important pieces of evidence scientists use to test the theory’s validity.[3] Therefore, it could be said that observation, in science, takes up the role as (ⅰ) the explanandum and (ⅱ) the evidence that evaluates a theory’s validity.

To give a thoughtful answer to the question, intuition and observation’s role in their respective fields must be examined in depth. Observation’s first role is self-evident: observation is that which is to be explained by scientific theories. However, the second role lacks some clarity. Due to the apparent vagueness of the term ‘evidence’, numerous philosophers, in their attempt to analyze the scientific method, have made many endeavors to precisely identify how observation’s evidential role in theory evaluation is to be understood (Chalmer, 2013; Staley, 2014). Of these efforts, I will discuss two of the most widely held considerations:

Hypothetico-deductivism and Bayesian Personalism.

Hypothetico-deductivism on Observation as Evidence. In Hypothetico-deductivism (HD), during their evaluation process, theories are subject to rigorous testing as scientists actively seek to falsify them by finding observational data that contradict their predictions (Popper, 2002). If a theory’s predictions are at odds with actual observations—and thus fail to satisfy the first TEP as laid out before—it is rejected regardless of whether or not it satisfies the rest of the TEPs.[4] By shaving off false theories through rigorous testing, scientists conversely seek to select theories that are consistent with empirical observations.[5] These unfalsified theories—although they never could, in principle, be proven to be true—are among the best, most plausible ones available to scientists.[6] As such, in the theory evaluation process, observation serves as the evidence—perhaps the most important one—that indicates which theories are false and which theories are most plausible.

Bayesian Personalism on Observation as Evidence. On the contrary, in Bayesian Personalism (BP), the main focus of theory evaluation is on who determines whether a theory must be accepted or not. A theory’s validity is determined by scientists and “ [the] subjective probabilities [, i.e.,] measures of subjective degrees of belief[, they assign to theories]” (Dorling & Miller, 1981, p. 110). In the evaluation process, empirical observation influences probabilities scientists assign to theories by strengthening or weakening scientists’ degree of belief in the theories in question (Dorling & Miller, 1981). As such, the evidential role of observation is to shape a theory’s subjective probability assigned by scientists, i.e., to persuade scientists.

Intuition’s Role: Explanandum and Evidence

In philosophy, it is widely accepted that “theories are designed to … explain [intuitions]” (Bealer, 1987, p. 312). Moreover, intuition—in philosophical argumentation—is presented as evidence for or against theories (Bealer, 1998; Pust, 2000). Thus, it could be said that intuition, in philosophy, takes up the role as (ⅰ) the explanandum and (ⅱ) the evidence that evaluates a theory’s validity.

The evidential role of intuition displays the same sense of ambiguity that was seen in the evidential role of observation. Therefore, I will further analyze the evidential status of intuition according to the two interpretations of the scientific method discussed before: HD and BP.

Hypothetico-deductivism on Intuition as Evidence. HD could characterize intuition’s role as evidence similar to how it describes the evidential role of observation in science. Philosophers “argue for [a theory] by showing that [what] it implies … is indicated by… intuitive judgements … [and] against the correctness of a theory by producing a … case [or cases] about which intuition disagrees with the theory in question” (Pust, 2000, p. 3). As a good theory must account for all the evidence, i.e., intuitions (Bealer, 1998), philosophers would reject falsified theories whose entailments contradict intuitive judgements. On the other hand, theories that are consistent with our intuitions would be considered to be strongly supported (Pust, 2000). Thus, intuition, in HD, could be interpreted as the evidence that either falsifies or strongly favors certain philosophical theories. HD’s interpretation of intuition’s evidential role seems to closely resemble its interpretation of observation’s evidential role: both intuition and observation either support or falsify theories in their respective fields.

Bayesian Personalism on Intuition as Evidence. In BP as well, intuition could be interpreted to take on an evidential role that closely resembles that of observation. When philosophers are persuaded by intuition to believe in the truth of a theory,[7] BP could emphasize the philosophers—the subjects in philosophical evaluation—and the evidential role intuition has in influencing their degree of belief. Intuition would form a theory’s subjective probability by strengthening or weakening a scientist’s degree of belief in the theory. Therefore, in BP, similar to how observation influences scientists, intuition would have the evidential role of persuading philosophers and thereby shaping a theory’s probability. As such, intuition seems to satisfy the first condition: intuition in philosophy, like observation in science, is the explanandum and the evidence used in theory evaluation in both HD and BP.

The Second Condition: Roles Only Intuition Serves

Intuition as the basis of philosophical theories

The epistemic weight intuition has in philosophical theory construction is quite distinct from that of observation in scientific theorization. As Bealer notes, philosophical inquiry starts from canvassing intuitions and proceeds to theorization by systematizing those intuitions (Bealer, 1998). Philosophical theories, in other words, are rooted in intuition. The only interpretation of the scientific method in which theories are derived from observations is inductivism (Chalmers, 2013). However, both Hypothetico-deductivists and Bayesian Personalists unanimously accept the glaring problems of induction presented by Hume and others (Dorling & Miller, 1981; Popper, 2002). Consequently, both views reject inductivism and would dare not describe scientific theories as being rooted in observational data. Thus, in both HD and BP, intuition serves an additional role that observation does not: intuition is the basis of philosophical theories.

Intuition in the Justification and Identification of TEPs and TCPs

Furthermore, intuition is responsible for much of the justification and identification processes of TEPs and TCPs. In many cases, philosophers—without rational justification—simply have the intuition that there are some theories that are better than others; that there are common qualities those theories possess which make them better; and perhaps most importantly, that philosophers know what those qualities are (Bealer, 1998; Carroll & Markosian, 2010). Simply put, much of the attempts at identifying and justifying TEPs rely on intuition.[8] For example, in discussing the reasons philosophers adhere to the principle of theoretical parsimony,[9] Carroll and Markosian write, “many philosophers just prefer a leaner, meaner ontology” (2010, p. 213).

Not only this, but the only evidence philosophers can offer for TCPs are exclusively their intuitions. Philosophers have the intuition that some truths are necessary for rational theory construction; that those truths cannot be false; and that philosophers know which ones they are. As Bealer writes, “[out of the] many alleged principles of logic and linguistic theory … [a philosopher] tell[s] which ones are true … ultimately by using intuition as evidence” (1987, p.310). Despite intuition’s intricate connection to TEPs and TCPs, observation enjoys no such relationship. Although observation can be used to evaluate theories, it itself cannot justify why it can be used as evidence. These are matters reserved for rational, and intuitive justifications.[10] Furthermore, empirical observation, by definition, has no part in constructing a priori principles of reason as well (BonJour, 1998).

Conclusion

Thus intuition’s role in philosophy can be summarized as the following:

intuition, in philosophy, takes up the role as (ⅰ) the explanandum, (ⅱ) the evidence that evaluates a theory’s validity, (ⅰⅰⅰ) the basis of philosophical theories, and (ⅳ) the evidence for the justification and the identification of TEPs and (ⅴ) TCPs.

There may be additional roles assigned to intuition and observation that I have failed to mention. Some may be assigned to both. However, as I have demonstrated, these three roles assigned to intuition that I have laid out are not to be found in observation. Moreover, it seems that these fundamental discrepancies are too great to be simply discarded as trivial. Consequently, regardless of any additional roles of intuition and observation I may have overlooked, intuition fails to fulfil the second condition. Therefore, the conclusion must be as follows: intuition in philosophy is not analogous to observation in science.

翻译

当被问及经验科学有什么特点时,人们常说它对观察的依赖可以作为答案。当对哲学提出同样的问题时,许多哲学家认为答案在于哲学依赖于我们的直觉。那么,自然会产生这样的问题:观察之于科学是否如同直觉之于哲学?为了回答这个问题,我将分别分析和比较科学和哲学中观察和直觉的作用。经过这样的考察,我得出的结论是,由于存在只有直觉而不是观察的角色,它们在各自领域的贡献并不相似。

然而,在讨论直觉和观察的作用之前,首先必须承认两者确实在科学和哲学探究中占有一席之地。因此,必须事先检查科学和哲学方法以及观察和直觉是否有助于它们。

科学理论与评价

在当代文献中,科学方法分为两个步骤:理论化和评估(Dorling & Miller, 1981; Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002)。科学家们首先通过假设合理的理论系统来开始他们的调查,这些系统根据理性来解释观察结果(Gieseler、Loschelder 和 Friese,2019;Popper,2002;Staley,2014)。在这个过程中,科学家们遵循我所说的理论构建原则(TCPs)。TCP 是允许科学家理性思考的必要理性原则[1] 。没有 TCP,即理性的规则,就不可能进行理性的理论化。因此,通过构建理性理论,所有科学家都遵循 TCP。

在科学家提出理论假设后,他们会辨别出最合理的理论。[2]他们 使用我所说的各种理论评估原则 (TEP) 进行评估:通常,科学家更喜欢与经验观察不矛盾的理论,这些理论是可证伪的、精确的、简约的,并且与已证实的理论一致(吉泽勒,洛舍尔德和弗里斯,2019 年;波普尔,2002 年)。展示 TEP 中列出的这些优点的理论,比未能做到这一点的理论更受青睐。由于理论构建和评价都与观察密切相关,因此得出观察是科学方法的核心的结论似乎是合理的。

哲学理论与评价

哲学家们普遍认为,哲学探究可以分为三个主要步骤:哲学家首先探索直觉,然后构建将它们系统化的理性理论,最后评估它们的合理性(Bealer,1998)。简而言之,哲学探究还涉及理论化和评估过程。

由于没有理性的基本原则就不可能有任何形式的理性理论化,因此哲学家在构建理性理论时也遵循 TCP。此外,哲学理论在构建之后会经历一个评估过程,在这个过程中,哲学家会应用他们自己的 TEP:通常,哲学家更喜欢在很大程度上与直觉一致、精确且在本体论上简约的理论(Carroll & Markosian,2010;Pust,2000) . 因此,直觉在理论构建和评价过程中也与哲学方法有着深刻的联系。因此,观察和直觉似乎分别在科学和哲学中占有一席之地。

有了这一点,为了回答哲学中的直觉是否类似于科学中的观察的问题,我将具体说明允许直觉类似于观察的条件。如果哲学中的直觉缺乏观察在科学中所享有的认知地位,或者反之亦然,那么这个问题就无法得到肯定的答案。因此,为了证明直觉的角色哲学与观察的角色科学相似,直觉必须满足以下两个条件:

哲学中的直觉不能缺少观察在科学中所扮演的任何角色。

2.直觉在哲学中的作用不能超过观察在科学中的作用。

第一个条件:观察和直觉的作用

观察的作用:解释和证据

如前所述,理论作为解释观测数据的解释器而存在。因此,在构建理论的过程中,观察承担了被解释的角色,即被解释的东西。由于理论的目的在于解释观察数据,因此观察是科学家用来检验理论有效性的最重要的证据之一。[3]因此,可以说 ,在科学中,观察起到了(ⅰ)解释和(ⅱ)评估理论有效性的证据的作用。

为了对这个问题给出一个深思熟虑的答案,必须深入研究直觉和观察在各自领域中的作用。观察的第一个作用是不言而喻的:观察是要被科学理论解释的。然而,第二个角色缺乏一些明确性。由于“证据”一词明显含糊不清,许多哲学家在试图分析科学方法时,已经做出了许多努力来准确地确定如何理解观察在理论评估中的证据作用(Chalmer,2013;Staley,2014) )。在这些努力中,我将讨论两个最广泛持有的考虑:

假设演绎主义和贝叶斯个人主义。

以观察为证据的假设演绎主义。在假设演绎主义 (HD) 中,在他们的评估过程中,由于科学家们积极寻求通过发现与他们的预测相矛盾的观察数据来伪造理论,因此理论受到严格的测试(Popper,2002 年)。如果一个理论的预测与实际观察不一致——因此不能满足前面列出的第一个 TEP——无论它是否满足其余的 TEP,它都会被拒绝。[4]通过严格的测试剔除错误的理论,科学家们反过来 寻求选择与经验观察一致的理论。[5]这些未经证实的 理论——尽管它们在原则上永远无法被证明是正确的——是科学家们可以获得的最好、最合理的理论之一。[6]因此,在理论评估过程中, 观察作为证据——也许是最重要的证据——表明哪些理论是错误的,哪些理论最有道理。

以观察为证据的贝叶斯个人主义。相反,在贝叶斯个人主义(BP)中,理论评估的主要焦点是由谁来决定一个理论是否必须被接受。理论的有效性由科学家和“[主观概率[,即]主观信念程度的度量[,他们分配给理论]”(Dorling & Miller, 1981, p. 110)来确定。在评估过程中,经验观察通过加强或削弱科学家对相关理论的相信程度来影响科学家分配给理论的概率(Dorling & Miller,1981)。因此,观察的证据作用是塑造由科学家分配的理论的主观概率,即说服科学家。

直觉的作用:解释和证据

在哲学中,人们普遍接受“理论旨在……解释[直觉]”(Bealer,1987,第 312 页)。此外,直觉——在哲学论证中——被呈现为支持或反对理论的证据(Bealer,1998;Pust,2000)。因此,可以说 直觉在哲学中扮演了(ⅰ)解释者和(ⅱ)评估理论有效性的证据的角色。

直觉的证据作用表现出与观察的证据作用相同的模棱两可感。因此,我将根据前面讨论的科学方法的两种解释:HD和BP,进一步分析直觉的证据地位。

以直觉为证据的假设演绎主义。HD可以将直觉的作用描述为类似于它描述观察在科学中的证据作用的证据。 哲学家“通过证明 [什么] 它所暗示的……由……直觉判断……来表明 [一个理论] 来为 [理论] 辩护……[并且] 通过提出一个……案例 [或案例]问题”(Pust,2000 年,第 3 页)。作为一个好的理论必须解释所有的证据,即直觉(Bealer,1998),哲学家会拒绝那些蕴涵与直觉判断相矛盾的被证伪的理论。另一方面,与我们的直觉一致的理论将被认为是得到强烈支持的(Pust,2000)。因此,在 HD 中,直觉可以被解释为证伪或强烈支持某些哲学理论的证据。HD 对直觉的证据作用的解释似乎与它对观察的证据作用的解释非常相似:

以直觉为证据的贝叶斯个人主义。在 BP 中,直觉也可以被解释为具有与观察非常相似的证据作用。当哲学家被直觉说服相信一个理论的真实性时,[7] BP 可以强调 哲学家——哲学评价的主体——以及直觉在影响他们的信念程度方面所起的证据作用。直觉会通过加强或削弱科学家对理论的相信程度来形成理论的主观概率。因此,在 BP 中,类似于观察如何影响科学家,直觉将具有说服哲学家的证据作用,从而塑造理论的可能性。因此,直觉似乎满足了第一个条件:哲学中的直觉,就像科学中的观察一样,是 HD 和 BP 理论评估中使用的解释和证据。

第二个条件:只有直觉服务于角色

直觉作为哲学理论的基础

哲学理论建构中的认知重量直觉与科学理论建构中的观察是截然不同的。正如Bealer 所指出的,哲学探究从探索直觉开始,然后通过将这些直觉系统化而进行理论化(Bealer,1998)。换言之,哲学理论植根于直觉。对从观察中得出理论的科学方法的唯一解释是归纳主义(Chalmers,2013)。然而,假设演绎论者和贝叶斯人格论者一致接受休谟和其他人提出的明显的归纳问题(Dorling & Miller, 1981; Popper, 2002)。因此,这两种观点都拒绝归纳主义,也不敢将科学理论描述为植根于观察数据。因此,在 HD 和 BP 中,

TEP 和 TCP 的理由和识别的直觉

此外,直觉负责 TEP 和 TCP 的大部分论证和识别过程。在许多情况下,哲学家——没有合理的理由——只是直觉地认为有些理论比其他理论更好;这些理论具有使它们变得更好的共同品质;也许最重要的是,哲学家知道这些品质是什么(Bealer,1998;Carroll & Markosian,2010)。简而言之,识别和证明 TEP 的许多尝试都依赖于直觉。[8]例如,在讨论哲学家坚持 理论简约原则的原因时,[9] Carroll 和 Markosian 写道,“许多哲学家只是更喜欢更精简、更简陋的本体论”(2010 年,第 213 页)。

不仅如此,哲学家可以为 TCP 提供的唯一证据完全是他们的直觉。哲学家的直觉是,某些真理对于理性的理论建构是必要的;那些真理不可能是假的;哲学家知道他们是谁。正如Bealer 所写,“[在]许多所谓的逻辑和语言理论原则中……[哲学家]告诉[s]哪些是正确的……最终通过使用直觉作为证据”(1987,p.310)。尽管直觉与 TEP 和 TCP 有着错综复杂的联系,但观察却没有这种关系。虽然观察可以用来评价理论,但它本身并不能证明为什么它可以用作证据。这些都是为理性和直观的理由保留的问题。[10] 此外,根据定义,经验观察也没有参与构建理性的先验原则(BonJour,1998)。

结论

因此直觉在哲学中的作用可以概括如下:

直觉在哲学中的作用是(ⅰ)解释,(ⅱ)评估理论有效性的证据,(ⅰⅰⅰ)哲学理论的基础,以及(ⅳ) 证明和识别 TEP的证据(ⅴ) TCP。

直觉和观察可能还有其他角色,我没有提到。有些可能会同时分配给两者。然而,正如我已经证明的那样,我提出的直觉的这三个角色在观察中是找不到的。此外,这些根本差异似乎太大了,不能简单地被视为微不足道而丢弃。因此,无论我可能忽略了直觉和观察的任何其他作用,直觉都无法满足第二个条件。因此,结论必须如下:哲学中的直觉不同于科学中的观察。

Footnotes:

1 The principles of logic, arithmetic, geometry, set theory, modality, probability, etc.

2 Dorling & Miller, 1981; Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002

3 Gieseler, Loschelder, & Friese, 2019; Popper, 2002; Staley, 2014

4 Popper, 2002

5 Popper, 2002

6 Popper, 2002

7 Pust, 2000

8 Concerning intuition’s contribution to the justification and identification of TEPs, I do not wish to imply that intuition is the only evidence philosophers can offer. Unlike TCPs, some philosophers do provide other rational justifications for some TEPs apart from mere intuitions.

9 The principle of theoretical parsimony states that theories, preferably, should be ontologically parsimonious and must not posit entities beyond necessity. This principle is stated in TEPs listed above.

10 Bealer, 1998; Carroll & Markosian, 2010

Bibliography

Bealer, G. (1987). The Philosophical Limits of Scientific Essentialism. Philosophical Perspectives, 1, 289-365. doi:10.2307/2214149

Bealer, G. (1998). Intuition and the Autonomy of Philosophy. In DePaul, M., & Ramsey, W. (eds.), Rethinking Intuition: The Psychology of Intuition and Its Role in Philosophical Inquiry. pp. 201-240.

BonJour, L. (1998). In Defense of Pure Reason. Cambridge University Press.

Carroll, J. W., & Markosian, N. (2010). An Introduction to Metaphysics. Cambridge University Press.

Chalmer, A. F. (2013). What is this thing called Science? (4th ed.). University of Queensland Press.

Dorling, J., & Miller, D. (1981). Bayesian Personalism, Falsificationism, and the Problem of Induction. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes, 55, 109-141. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4106855.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fbasic_SYC-5187% 252Ftest&refreqid=excelsior%3A034b8233ec77dfcbdabe67ef272d7197

Gieseler K., Loschelder D.D., & Friese M. (2019) What Makes for a Good Theory? How to Evaluate a Theory Using the Strength Model of Self-Control as an Example. In Sassenberg K., & Vliek M. (Eds) Social Psychology in Action. pp. 3-21

Popper, K. (2002). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (2nd ed.). Routledge. Pust, J. (2000). Intuitions as Evidence. Nozick, R. (Ed.) Routledge.

Staely, K. W. (2014). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Cambridge University Press